When Will Usain Bolt’s 100m Record Be Broken?

Photo Credit: Sky News

The 100m sprint certainly isn’t a ball sport, but the race that determines the title of Fastest Man on Earth definitely deserves an analysis.

It has been over 14 years since Usain Bolt set the 100m world record by clocking in at an astonishing 9.58 seconds at Olympiastadion, Berlin. Back in 2009, many may have expected the progression of record breaking 100m times to continue. However, that trajectory never materialized, and the only individual who has even come close to Bolt's remarkable record time is Bolt himself. This made me wonder: Is it possible to estimate when someone will beat Bolt’s 100m record?

In this analysis, I will delve into the data encompassing 1262 men's 100m outdoor sprints, all electronically timed at under 10.0 seconds and executed with a maximum permissible tailwind of 2.0 m/s (the threshold for record-qualifying times). The aim is to make an estimation of when someone will eventually surpass Bolt's record.

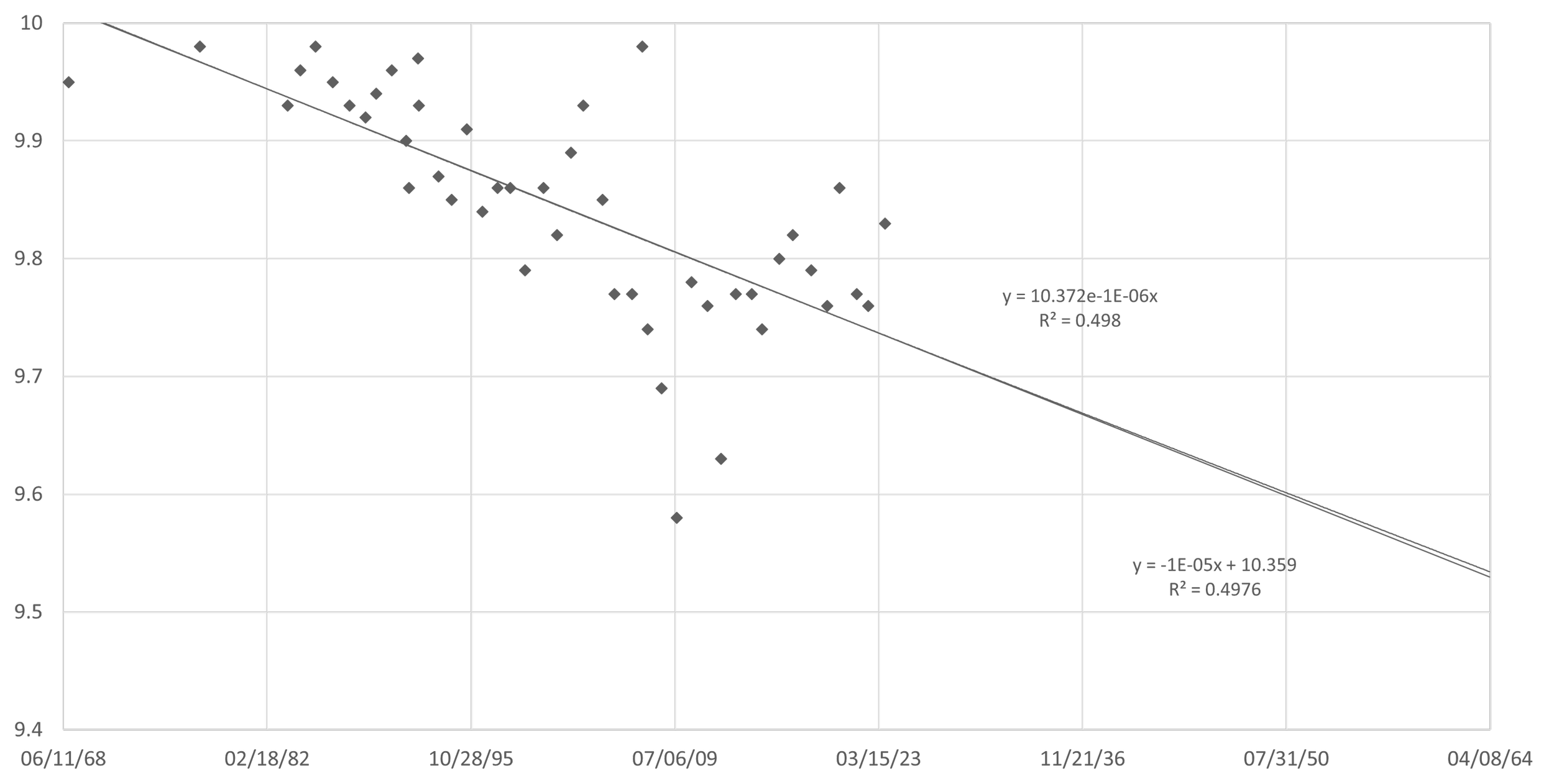

Examining the fastest 100m sprints ever in Chart 1, we see that the data points tend to cluster, forming some sort of a right triangle, with the right angle found at the intersection of March 2023 and the 10.0-second mark. Within this right triangle, the hypotenuse consists of exceptional record-breaking performances.

Chart 1: 1262 100m sprints of less than 10.0 seconds, electronically recorded with a maximum tailwind of 2.0 m/s. The y-axis is the sprint time and the x-axis is the date.

I’ve annotated some of the record breaking runs and the effects of altitude and wind are evident. The two record-breaking runs by Jim Hines in 1968 and Calvin Smith in 1983 took place at elevations of 7,350 feet and 6,035 feet, respectively. Furthermore, five of the six annotated runs had tailwinds ranging from 0.1 m/s to 1.5 m/s. Usain Bolt’s 9.69 in Beijing in 2008 is the only annotated run at moderate elevation (161 feet) with no tailwind.

Now, let's take a closer look at the hypotenuse of this triangle.

Chart 2: Record breaking or era-defining 100m sprint times; y-axis is the sprint time and x-axis is the date.

Exponential decay and linear trendlines present along with R-squared and equations.

The progression from 1968 to 2012 demonstrates a remarkable linearity. The exponential decay and linear fits in Chart 2 exhibit striking similarity, indicating a steady reduction in the world record time at a rate of approximately 0.00825 seconds per year (equivalent to 2E-05 seconds per day).

Nonetheless, this linear advancement has come to a halt since the conclusion of the Usain Bolt Era. As progress has plateaued or even exhibited signs of regression over the last decade, I see the need to add more recent data points to improve the predictive power of the fitted models.

Looking at the best annual 100m sprint times in Chart 3, Bolt’s 9.58 sticks out as a massive outlier. If the best annual times continue at the pace they have trended over the past 55 years, it may take another 30 years for a sprinter to match Bolt’s level. Furthermore, it's reasonable to anticipate that when this feat is eventually matched, the combination of high altitude and a tailwind approaching 2.0 m/s will be a significant contributing factor.

Chart 3: The best annual 100m times with exponential decay and linear fits. The y-axis is the sprint time and x-axis is the date.