Why Do Curveballs Have a Reverse Platoon Advantage?

Photo Credit: Yong Kim/Staff Photographer

A recent post by Tom Tango about platoon splits by pitch type revealed that changeups and curveballs are the two pitches with the most significant reverse platoon advantage - that is, right-handed pitchers’ changeups and curveballs are more effective against left-handed batters, and left-handed pitchers’ changeups and curveballs are more effective against right-handed batters. Changeups tail to the arm side and away from batters on the opposite side of the pitcher, so a reverse platoon advantage there is not surprising. But why are curveballs more effective against batters with the opposite handedness of the pitcher? And how can pitchers use that to optimize their execution of curveballs?

To investigate this, I looked at the 14,000 plate appearances (PAs) in 2023 that ended in curveballs and split them into “same” and “opposite” based on the handedness of the pitcher and batter. For the analysis, I grouped curveballs and knuckle-curves together.

Table 1: Platoon advantage of curveballs

As seen from Table 1, batters of the same handedness as the pitcher actually have a worse expected weighted on-base average (xWOBA) in PAs ending in curveballs (.263) relative to batters of the opposite handedness of the pitcher (.289). That significant 26 point difference tells us that curveballs do have the normal platoon advantage when it comes to ending an at-bat. Tango’s blog post focused on the run value of the pitches, incorporating every pitch of every PA, instead of just the pitch that ended the PA, which xWOBA focuses on. Thus, for curveballs to have a reverse platoon split overall and a traditional platoon split in the pitches that end PAs, curveballs must have a significant reverse platoon split early in counts.

The Importance of Called Strikes for The Reverse Platoon Effect

Curveballs against batters of the same handedness have a called strike rate of 16.26% and a swinging strike rate of 11.65%, whereas curveballs against batters of the opposite handedness have a called strike rate of 18.85% and a swinging strike rate of 9.64%. For reference, the MLB called strike rate in 2023 is 16.44% and the MLB swinging strike rate is 10.61%. Hence, the curveball reverse platoon effect is heavily reliant on getting called strikes, with the 2.59% higher called strike rate more than offsetting the 2.01% lower swinging strike rate.

So how can a pitcher get more called strikes on his curveballs? With very little difference in pitch characteristics (horizontal break, vertical break, release speed, spin rate, release point) between called strikes and non-called strikes, I focused my called strike analysis on pitch location.

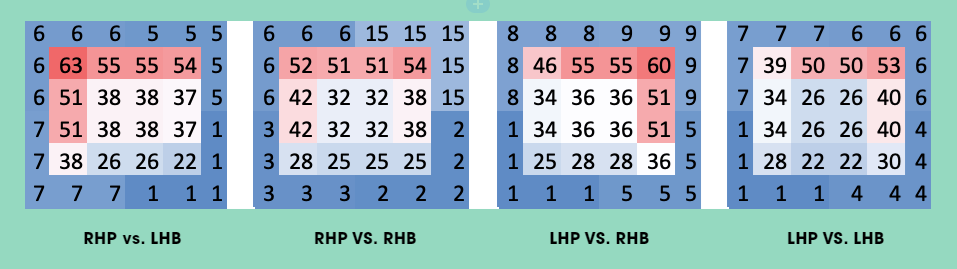

Figure 1: Called strike rate (%) per pitch zone (the middle 16 rectangles represent the strike zone) for each handedness matchup, as seen from the catcher’s perspective.

As illustrated in Figure 1, right-handed pitchers (RHPs) are getting a 63% called strike rate on curveballs against left-handed batters (LHBs) in the top left portion of the strike zone, as well as more than 50% called strikes in five other zones at the top and outside portion of the plate. However, against right-handed batters (RHBs), RHPs are only getting called strike rates higher than 50% in four zones, all at the top of the strike zone.

Left-handed pitchers (LHPs) are getting a called strike rate of 60% against RHBs in the top right portion of the strike zone, as well as more than 50% called strike rates in four other zones at the top and outside portion of the plate. Against LHBs, however, they are only getting called strike rates of 50% or higher in three zones, at the top of the strike zone.

Evidently, pitchers are significantly better at getting called strikes with curveballs against opposite handed batters, especially up and away from the batter.

Why could this be? Early in the count, batters are usually looking for fastballs, so when the curveball from an opposite handed pitcher starts far up and away, batters are likely to give up on the pitch. The backdoor curveball then breaks into the top and outside portion of the strike zone for a called strike.

On the other hand, batters of the same handedness of the pitcher see the frontdoor curveball starting directly at them. They track the pitch spin closely since they know they need to get out of the way (or take a Hit By Pitch off the elbow guard) if it is a fastball, and are able to pick up the spin on the ball in time to react to curveballs that break back over the plate.

However, with two strikes, batters on both sides are much less likely to give up on pitches. The league has a 4.61% called strike rate with two strikes. Nobody likes to strike out looking, so in two-strike counts, batters tend to track curveballs longer and swing at curveballs that make it back to the strike zone. With two strikes, the swing-and-miss pitch is far more valuable, and thus curveballs carry the traditional platoon advantage.

What Does This Mean For Pitchers?

Curveballs have a reverse platoon split because pitchers can more effectively get called strikes with them against batters of the opposite side. Until batters adjust their approach and look for more curveballs early in the count, pitchers will continue to exploit opposite handed batters with curveballs up and away. However, curveballs do not have a reverse platoon advantage when it comes to finishing off PAs. In pitches that end PAs, curveballs perform better against batters of the same handedness as the pitcher, due to their ability to generate swings and misses.